I read an article about a mother Orca whose newborn calf had died. She continued to swim with their body, held aloft by her nose, for three days. A few times the calf slipped away, and she dove to retrieve them before finally letting the deteriorating body sink to the bottom. Whales control their heartbeat as they descend the depths to accommodate the pressure of the water, sometimes reducing to just a few beats per minute. I wondered about the grieving Orca, her heart slowing to a near stop before she carried her newborn to the surface. But their hearts did not quicken together.

The sound of a whale’s heartbeat can be recorded from miles away, but can you measure the sound of heartbreak?

As I slowly eased my body into the frigid water that morning in May, I remembered my dream of “the Harpees.” The only other people approaching the water were an elderly woman and a couple of teenaged boys, daring each other. I stood at the shore breathing deeply before slowly wading in. When I softened my chest it rushed out of me, and I floated until my toes were nearly numb. I came out to warm up in the sun but felt compelled to do it again. This time I didn’t hesitate and walked confidently all the way up to my neck. I caught a strong chill and didn’t stay long, but when I lay out on the sand it felt as if my body was filled with the ocean.

When I got home I opened my sketchbook where I found a drawing dated from 12/23/22, the morning after the dream.

I added some color and felt the movement of my hand, and the shape of the mammal that leapt out of the water. My mind filled with the vastness of the dock and I finally understood what it meant.

He corrected me, and said that the East River was “not actually a river, it’s a tidal strait.” But I prefer the term Tidal Estuary. It flows from the New York Harbor to the Long Island Sound. Prior to colonization the whole length of it was bordered by marshes and wide, shallow banks.

The waterway was narrowed and deepened to accommodate larger ships porting in lower Manhattan, resulting in a quickening of the currents.

As you might imagine, industry and manufacturing devastated the ecosystem.

The waters used to teem with fish, and beds of oysters and seagrass lined the floor of the channel. Even whales and seals would navigate its forty mile expanse. In just over two hundred years it was overcome by algae blooms and darkened by waste.

The Gowanus Canal and Newtown Creek, which extend into the manufacturing zones of Brooklyn and Queens, are the most polluted. Thick layers of toxic sediment settled at the bottom have been deemed by some as too hazardous to disturb.

When I was in my early 20s I lived in Greenpoint Brooklyn, a few blocks from Newtown Creek. I remember sitting at the edge of the water, watching holographic plumes float along the surface out to the East River. The intersection of the two flows created a visual effect of the water twisting itself into tiny spirals. It looked beautiful.

The Lenape called it Muhheakunnuk, The River that Runs Both Ways. Changing direction with the tide, it empties and fills itself with the contents of the Atlantic Ocean and the Sound.

I regained the ability to swim in a saltwater pool. Aqua fitness. After several years of recovering from injury, my arms were weak and delicate. In the shallow depth I kept my fingers open while I paddled at first, then closed and cupped, and after several months I was able to carve them forcefully through the water. I could move myself through the water, and I realized I could probably swim safely in the ocean again. I was deep in this thought when he appeared.

The first time I met Gregory it scared the shit out of me. I was a bit rude actually, but in my defense I was still getting used to ghosts. By this time we were well acquainted and I was glad he came alongside me in the pool. I wondered, would he like to join me?

I invited him to feel my arms slip through the water.

A peculiar, viscous sensation surged into my body until my bones hummed. A haze settled over my vision. Our arms lengthened and became the tentacles of an octopus, snapping in spiral movements unsuited to hinging joints. We gathered waves that splashed against the inner wall of the pool and curled back onto our faces. Heat flashed across my skin, a timelapse image of a bud unfurling.

I closed my eyes and felt my awareness drop into the water. My lips tingled and the breath stopped for a moment as my ribs contracted, until it poured out from my navel and the class was over. I stretched silently and glided to the far side of the pool. I traced my fingertips along the cool tile and collected myself before climbing out.

There's a particular translation from some of the texts about Karma that refers to "the dungeon of the ribcage." A common interpretation refers to our identification with the physical body.1 The body is only a vessel for our consciousness, but we see its image before us in the mirror and claim it instinctively. How do we confront this illusion? Perhaps with time we come to realize that the physical form is the most limited aspect of our being, that will inevitably break down, become ill, and cease to breathe, and instead begin to identify as the one inside the body.

We learn to track the interior sensations and movements of energy, the subtle body, and slowly unlock the flow of vitality in the spine. But dropping into this current reveals that this is not who we are either. In the internal space we’re still watching the expressions of personality— this life. Pulling back into the awareness of the one who is observing, we may become frightened by losing our individual identity. What remains when the body, the experiences, the emotions, the thoughts, and the mind are left behind?

It is said that the true Self is unchanging, the part of you that witnesses all of the above. In other words, if it changes, moves, creates, destroys, or acts, it is not the Self. Which means that Karma is not us either. Yet interestingly, the venue of Self is the only one where Karma can be dissolved.

The Self of this definition is pure consciousness: shining, infinite, and timeless. We can enter this remembrance in small but potent glimpses in meditation. With some grace we may linger for a while and feel a resonance of love which clarifies what is real and unreal.2

It is in the spaces between that we find such portals— between breaths, between thoughts, between heartbeats— but none are as distinct as the space between one life and the next. When the body dies all that remains is the Self, which has dissolved into everything.

When the doorway opens to me I can see my body from the outside, resting peacefully. Some say grief is a form of love, and maybe it’s an anticipatory grief, because in those moments I have nothing but appreciation for this body that will whither away and disappear. I feel only compassion for the personality and memories, which will also disappear. If the fear of falling apart can be navigated, this love flows back into the body-mind and something like bliss emerges. Then that slips away too.

You might think that being able to talk to the dead would make you less afraid of dying, but it can have the opposite effect. Often the spirits one encounters are still very attached to the physical. They seem lost, afraid, confused, or just stubborn. They may need someone they recognize from the other side to help them let go. We all want “a good death,” but any death can be a good one if you can recognize what is unchanging.

Yes, when you commune with the dead it’s useful to talk to those who have found their way peacefully too. Fortunately it appears that some choose to hang around for this exact purpose.

I suppose it’s only fitting that I would swim with ghosts, because my own complicated affair with water began with almost drowning. I had loved to swim from a young age, but on this occasion the water overpowered me and I had to decide if I wanted to live. It was necessary to let go in order to find my way to safety, and I was afraid of the water for many years after that.

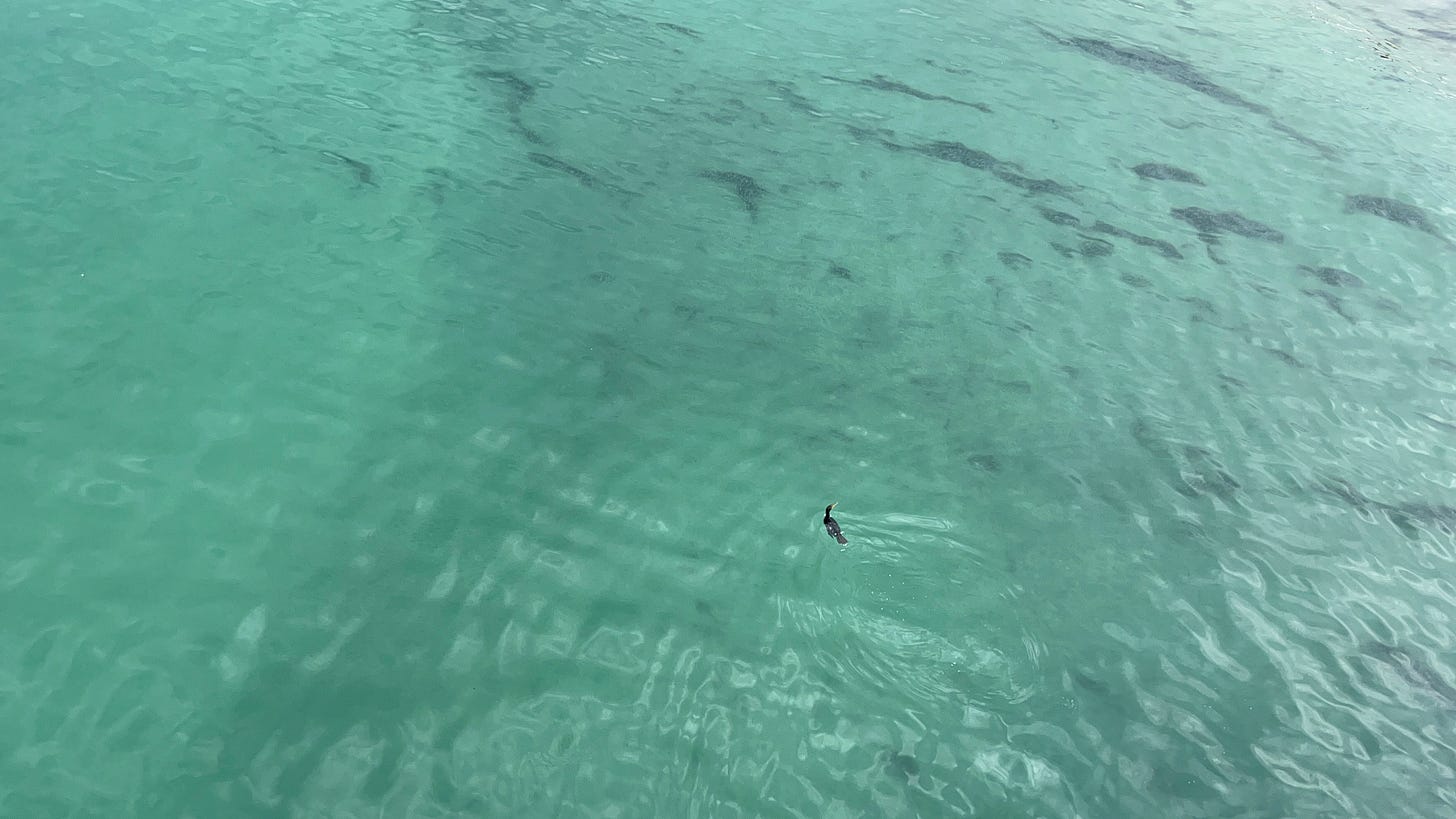

Our relationship now is one of respect and reverence, the kind of trust that can only come after a rupture. I swim in the ocean as often as I can but it feels like greeting a long-lost friend every time. Swimming is probably the wrong word— maybe it’s the equivalent of a mindful walk but in the water.

No, that’s not it either.

It’s a prayer. An expression of gratitude and a request. A celebration of life and a promise to pay attention. A recognition that our contents are the same.

Sometimes these words echo in my mind like verses. It’s intimate to be alone here.

The sand shifted abruptly from under my feet, and I remembered the rip current watch as I pushed into the surf in Nags Head, NC. It was early in the morning and unusually chilly for July. The seagrass was sharp as it wrapped around my ankles, along with the occasional jolt from a tiny jellyfish.

I didn’t venture out too deep but I did lift my hips up, and face my body towards the sun. The water glimmered, shining from all directions. My head tilted back until my ears eased below the surface of the water and I quieted my mind to listen.

It seemed so obvious, and in the eruption of sound behind me I almost thought it was the seagrass laughing instead of children playing. As the waves grew larger I stood up again, jumping high and throwing myself into walls of water. Time expanded, and now my fingers were pruned and pale.

The wind was playing too. After a few more splashes of water up my nose it was time to find my way home.

But before I did, I gave it to the water.

Next Post > IX: Afterbirth

You can let Simrit tell you about it

Or you can explore further in the Dṛg-Dṛśya-Viveka (or through these talks), Meditation for the Love of It by Sally Kempton, The Luminous Self by Tracee Stanley, and Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, among others.